DA Rollins is on the right path in criminal justice reform

To read on the Boston Globe website click here

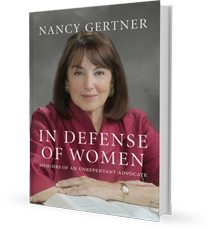

By Nancy Gertner

Just when it seemed everyone was open to new ideas about criminal justice, after last year’s reform bill, Thomas Turco, the state secretary of public safety and security, rehashed old tropes, and worse, old politics in blasting Suffolk District Attorney Rachael Rollins’s prosecution plans. Turco’s broadside was released to the press without notice to the new DA; Rollins’s reply was swift, attacking Governor Charlie Baker for authorizing it. The reported rapprochement between the two officials, while admirable, shouldn’t obscure some of the larger issues the dust-up reveals.

Turco criticized Rollins’s “decline to prosecute” list, ignoring crucial details in her 65-page plan. A Suffolk prosecutor was obliged to decline or divert certain offenses unless he or she got permission from a more experienced supervisor. (Turco ignored the “unless” clause.) The list consists of nonviolent crimes involving drugs, property, and offenses like driving with a suspended license, and it makes sense. Too often these offenses are driven by poverty, substance abuse, mental health issues, housing, or food insecurity – better dealt with through diversionary programs and not punishment.

Another focus of Turco’s ire was the DA’s admonition to look to relatively recent prior convictions – within the previous 36 months – in deciding how serious the current charge should be. Too often a prosecutor seeks a more severe sentence or charge based on an old conviction, when the defendant was a young man, for example, ignoring what had been going on in his life in the interim. Turco also challenged the fact that the DA encouraged prosecutors to look not only to drug quantities in deciding whether to charge possession with intent to distribute drugs, but also to other evidence of substantial dealing. Too often the drug-quantity focus meant throwing the book at the lookout sitting on a drug stash over which he has no meaningful responsibility and from which he derives no profit. In any case, these policies were presumptive, meaning an ADA could consult with a supervisor about whether to apply them in an individual case.

Rollins’s policies, Turco insists, upset the balance of the criminal justice bill, between reducing “unintended long-term consequences” of imprisonment, and the government’s responsibility to ensure public safety. The latter, Turco says, Rollins seemed to “categorically” dismiss.

Categorically dismiss? The only one “categorically” dismissing public safety concerns was Turco, not Rollins. Rollins’s policies were drafted after consulting leading experts and analyzing data. They are subject to continuing review. They parallel programs in jurisdictions across the country that have had positive effects. Their rationale is straightforward — to assure that prosecutorial resources are allocated where they make the most sense: violent crime and serious drug traffickers.

Most of all, Rollins’s plan addresses issues that Turco has “categorically dismissed” — racial disparities in the criminal justice system. Police charged trespass, resisting arrest, and disorderly conduct against people of color three time as often as whites. Blacks were charged with driving offenses four times as often as whites. And every conviction, no matter how petty, has serious consequences, impairing a defendant’s access to education, jobs, and housing.

If Turco wants to look critically at the state of the Massachusetts criminal justice system, there are better places to start. Take mandatory minimum sentences, which this administration supports, even though they have little or no impact on recidivism or promoting public safety. Or consider life without parole: Massachusetts ranks fifth in the country in the rate of prisoners serving life and virtual life. The result is an aging prison population imprisoned at great cost, past their proclivity — event their physical ability – to commit crimes. Massachusetts leads all in sentencing disparities between Hispanics and whites and ranks among the highest in black/white sentencing disparity. Given this history, Turco should urge the governor to reevaluate his commutation and clemency policies. In the four years the governor has been in office, he has granted none.

Since Turco’s agency has no jurisdiction over the elected DAs, his letter was completely gratuitous. He didn’t bother to criticize former DA Dan Conley when he implemented a similar policy, dismissing 12 percent of petty offenses. Nor did Turco opine about the Hampden DAwhen the US Department of Justice and the Massachusetts attorney general charged police officers involved in misconduct because the DA would not; or the Plymouth DA’s office when a racist e-mail and sexual harassment scandal erupted.

No, Turco set his sights on a new DA, four months in office, trying out a thoughtful plan and yes, an African-American woman. The governor was right to apologize for Turco, but that’s only the start.